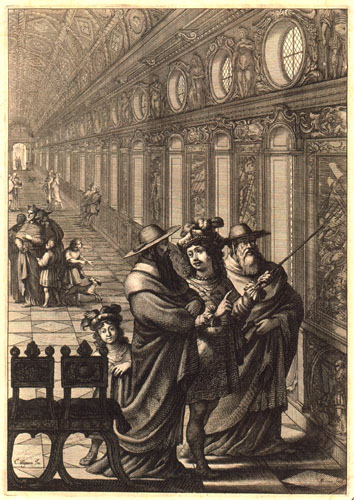

Illustrations from Jean Chapelain'a work

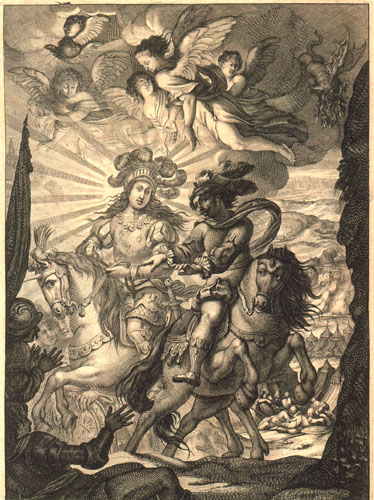

"La Pucelle ou la France Delivree"

The following 11 illustrations are from the private collection of

Mr. Ronald Aksnowicz from the Chicago, Illinois area.

Thank you, Mr. Aksnowicz for sharing these impressive original images with the world.

(The following information comes from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.)

Jean Chapelain

(December 4, 1595 - February 22, 1674) was a French poet and "man of letters," the son of a notary for whom Colbert may have once been employed. Chapelain was born in Paris.His father destined him for his own profession; but his mother, who had known Ronsard, had determined otherwise. At an early age Chapelain began to qualify himself for literature, learning, under Nicolas Bourbon, Greek and Latin, and teaching himself Italian and Spanish.

Having finished his studies, he was engaged for a while in teaching Spanish to a young nobleman. He was then appointed tutor to the two sons of a M. de la Trousse, grand provost of France. Attached for the next seventeen years to the family of this gentleman, the administration of whose fortune was wholly in his hands, he seems to have published nothing during this period, yet to have acquired a great reputation as a probability.

His first work given to the public was a preface for the Adone of Marini, who printed and published that notorious poem at Paris. This was followed by an excellent translation of Mateo Aleman's novel, Guzman de Alfarache, and by four extremely indifferent odes, one of them addressed to Richelieu. The credit of introducing the law of the dramatic unities into French literature has been claimed for many writers, and especially for the Abbé d'Aubignac, whose Pratique du théâtre appeared in 1657. The theory had of course been enunciated in the Art poetique of JC Scaliger in 1561, and subsequently by other writers, but there is no doubt that it was the action of Chapelain that transferred it from the region of theory to that of actual practice.

In a conversation with Richelieu in about 1632, reported by the abbé d'Olivet, Chapelain maintained that it was indispensable to maintain the unities of time, place and action, and it is explicitly stated that the doctrine was new to the cardinal and to the poets who were in his pay. French classical drama thus owes the riveting of its fetters to Chapelain. Rewarded with a pension of a thousand crowns, and from the first an active member of the newly constituted Academy, Chapelain drew up the plan of the grammar and dictionary the compilation of which was to be a principal function of the young institution, and at Richelieu's command drew up the Sentiments de l’Académie sur le Cid.

In 1656 he published, in a magnificent form, the first twelve cantos of his celebrated epic La Pucelle, on which he had been engaged during twenty years. Six editions of the poem were disposed of in eighteen months. But this was the end of the poetic reputation of Chapelain, "the legist of Parnassus." Later the slashing satire of Boileau (in this case fairly master of his subject) did its work, and Chapelain ("Le plus grand poète Français qu’ait jamais été et du plus solidejugement," as he is called in Colbert's list) took his place among the failures of modern art.

Chapelain's reputation as a critic survived this catastrophe, and in 1663 he was employed by Colbert to draw up an account of contemporary men of letters, destined to guide the king in his distribution of pensions. In this pamphlet, as in his letters, he shows to far greater advantage than in his unfortunate epic. His prose is incomparably better than his verse; his criticisms are remarkable for their justice and generosity; his erudition and kindliness of heart are everywhere apparent; the royal attention is directed alike towards the author’s firmest friends and bitterest enemies. To him young Racine was indebted not only for kindly and seasonable counsel, but also for that pension of six hundred livres which was so useful to him. The catholicity of his taste is shown by his De la lecture des vieux romans (pr. 1870), in which he praises the chansons de geste, forgotten by his generation.

Chapelain refused many honors, and his disinterestedness in this and other cases makes it necessary to receive with caution the stories of Ménage and Tallemant des Réaux; who assert that he was in his old age a miser, and that a considerable fortune was found hoarded in his apartments when he died.

There is a very favorable estimate of Chapelain's merits as a critic in George Saintsbury's History of Criticism, ii. 256-261. An analysis of La Pucelle is given in pp. 23-79 of Robert Southey's Joan of Arc. See also Les Letters etc Jean Chapelain (ed. Philippe Tamizey de Larroque, 1880-1882); Letters inédites.... D Hurt (1658-1673, ad. by LG Pellissier, 1894); Julien Duchesne, Les Poèmes épiques du XVII' siècle (1870); the abbé A Fabre, Les Enémis de Chapelain (1888), Chapelain et nos deux premières Académies (1890); and A Muehian, Jean Chapelain (1893).

This entry was originally from the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica.

Jean Chapelain

wrote "La Pucelle ou la France Delivree" in 1656 to honor his patron who was a descendent of the Count Dunois, the Bastard of Orleans. This ponderous work was written to honor Dunois and Joan was only one of the supporting characters. In this poem the villains are the Duke of Bedford and Agnes Sorel. The fist volume of this epic poem although popular with the masses was roundly 'pained' by the then famous arbiter BOILEAU. Thus the remaining portions of Chapelain's work were not published until 1882.

Claude Vignon

, (b. 1593, Tours, d. 1670, Paris) is the artist who made the designs or possibly even oil paintings of the originals images.French painter and engraver, born in Tours and active mainly in Paris. His richly eclective style was formed mainly in Italy, where he worked c. 1616-1622, and his openness to very diverse influences was later fuelled by his activities as a picture dealer. Paradoxically, in view of his varied sources of inspiration, his style is the most distinctive of any French painter of his generation - highly colored and often bizarrely expressive. Elsheimer and the Caravaggisti were strong influences on his handling of light, and his richly encrusted brushwork has striking affinities with Rembrandt, whose work he is known to have sold. Vignon is said to have fathered more than twenty children by his two wives, and his sons Claude the Younger (1633-1703) and Philippe (1638-1701) were also painters.

Bosse, Abraham

(b. 1602, Paris, d. 1676, Paris) is the engraver who made the copper plates from these prints. As you can imagine it took no little skill to make the plates. You will find both names in the composition on each engraving. Vignon on the left and Bosse on right near the bottom of each design.French engraver. His large output, (more than 1.500 prints) provide a rich source of documentation on 17th-century French life and manners. Many of his engravings are genre scenes, and even his religious works are in modern dress. Bosse taught perspective at the Académie Royale from its foundation in 1648 until 1661, when he was expelled for quarrelling with his colleagues over his opposition to Le Brun's dogmatic theories. He wrote treatises on engraving, painting, perspective, and architecture and he occasionally painted.

There were more than these 11 images in the original series by Abraham Bosse. If any one has a copy of the missing images please contact THE SAINT JOAN OF ARC CENTER at stjoan@nmia.com

Title page of the poem. "Joan raises up a fallen France"

A descendant of the Count Dunois explains the action occurring in Claude Vignon's oil paints. (?)

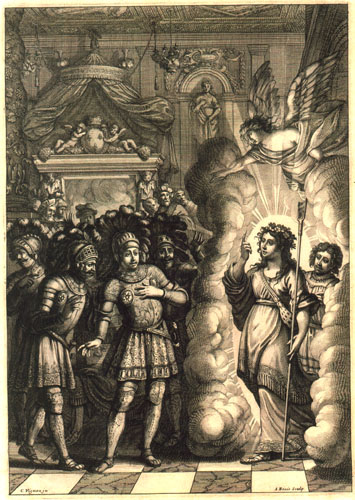

The Dauphin receives the 'sign' that he is the true heir to the throne of France.

The wind changes direction through Joan's prayer (?)

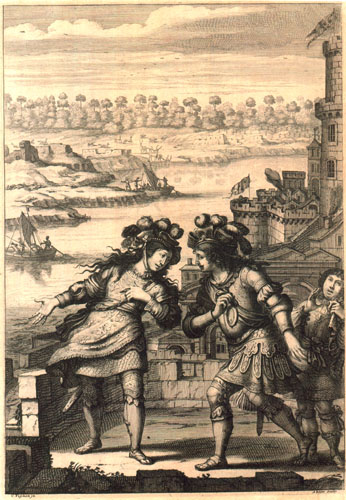

Joan orders all the 'camp followers' away from the army.

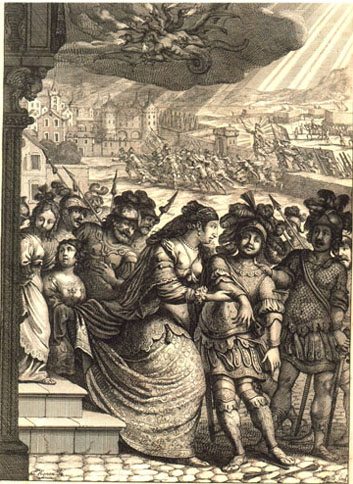

Dunois is wounded during the siege of Orleans.

(In reality Dunois was wounded in the foot before Joan ever came to Orleans.)

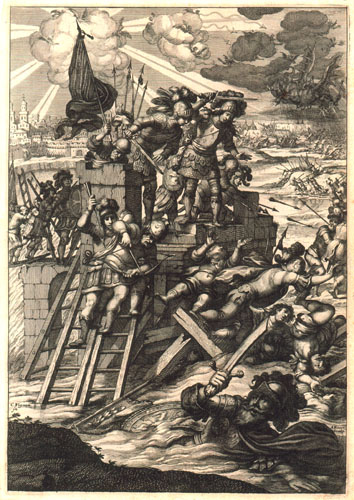

Joan witnesses the drowning of Glasdale and the other English soldiers.

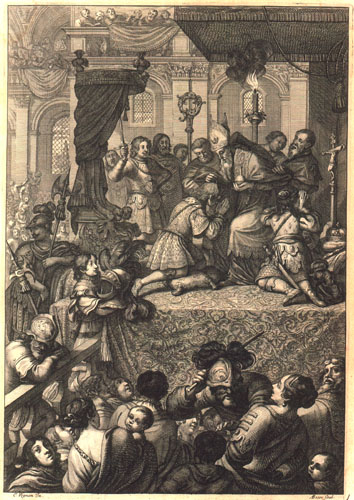

The Coronation of King Charles VII.

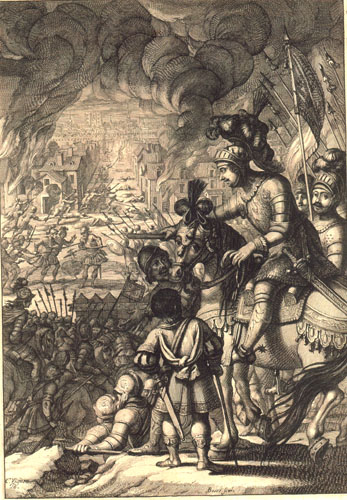

Dunois directs the attack on Paris.

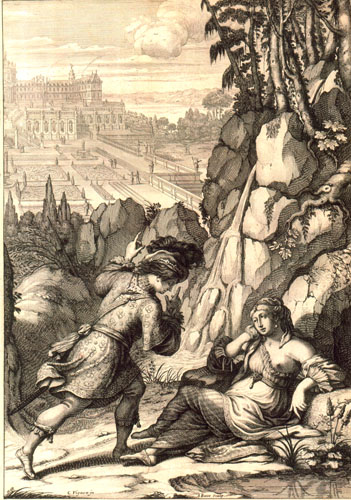

Joan reprimands Agnes Sorel.

Joan is captured at Compiegne.